A Look at The Inappropriate Discrediting of Day Services Programs

Adult day programs and their contributions to the long-term community and to America’s neighborhoods are not new. From the shores of the Florida gulf to the top of Green Bay, Wisconsin these initiatives have held families together and provided meaningful clinical elements to treatment plans.

Of course, program types and missions vary. In the U.S. State of Georgia and other places, adult day care programs can be attended by residents admitted into Medicaid-funded personal care homes up to twice per week. Both environments are reimbursed. This adds to the cadre of services provided that assist in managing challenging behaviors, nutritional needs, medication understanding, and physical rehabilitation routines.

Another program type is the Neurological Cognitive Day Treatment Program, (a/k/a Neuro Cog). While available to those who are already living in supervised residential environments, they are rarely if ever a complimentary service. It is expected there would be a separate charge. Why is that?

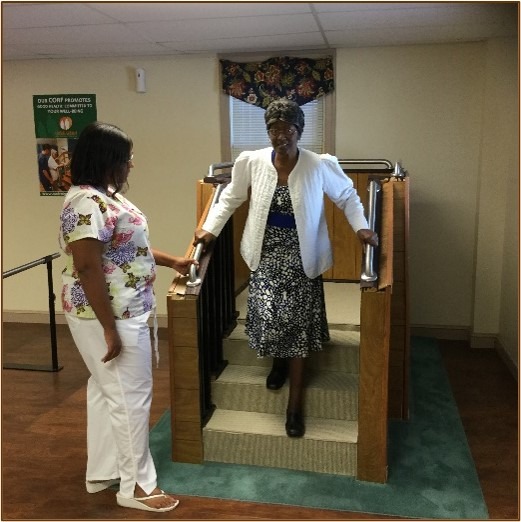

While true that residential care environments provide a degree of supervision, nutritional and medication management, they are not typically loaded with the work of skilled professionals all day long. The only exception would be the skilled nursing center. These professionals who are routinely a part of the Neuro Cog programming include licensed professional counselors, recreational therapists, rehabilitative therapists, psychologists, certified personal trainers, and in some states medication education techs. The schedule regularly includes activities in outside environments. All of this is known to the neurologist, psychiatrist, and/or physical medicine physician who typically write the orders for enrollment into this program.

Occasionally the assumption is made by a bill reviewing agency, insurance adjuster or other party that the service should be or is an automatic part of what is provided in the residential care environment. Unless specifically indicated by the care provider, this is normally a mischaracterization.

The residential rate agreed to would not have considered the vast services available in the Neurological Cognitive Day Treatment Program that complements the overall care, recovery, and rehabilitation of the program enrollee. Neither would it have considered the additional cost of involving the work of other professionals, all combined into one day-time initiative.

In some cases, a lower rate than what the market would tolerate has been negotiated for the residential placement. Surely in these instances, said the negotiated rate would not consider the addition of the cognitive initiative.

Additionally, there are other challenges for those who intentionally seek to group residential and day services together to achieve certain financial goals. When we deliberately mischaracterize how an entity provides or bills for services and in the process cost them revenue via arbitrary actions to which they did not contribute, can “lost-profit” litigation be far behind. How much better it is for parties on both sides of the financial side of this service to come together and negotiate a price-pattern. In the end, this might lead to more savings than rising in the cost of care.